Creating Quality

This entry is Part 4 out of a 4 part series on quality. Here is Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

Whether reading, listening, watching or just consuming in general, all of us appreciate quality when we can get it. But there's more to quality than just consumption.

While we all enjoy consuming quality, there is a deeper satisfaction in having created it. Creation is an act of expression, and to express something is to extend it beyond yourself. This is the opposite of consumption. Creation is the act of crafting an experience not just for yourself, but for another.

Though the act of creation itself is easy enough, what remains far more difficult is creating quality. Quality requires a labour, an effort, a toil. Fortunately, this toil is never without direction.

Based on what we consume, we have all manufactured in our minds a standard of what we call quality; this standard is so familiar to us that we instantly recognise it when we see it, and even more so when we don't. Significantly, this standard is also our unconscious guiding herestic when we ourselves turn to creating that which we consume. In other words, this is our benchmark.

Although we are aiming for this benchmark, it is important not to simply replicate or reproduce works which meet it. Apart from ethical reasons, imitation is unable to produce true quality because whatever is created already exists. This is because inherent within the idea of quality is the concept of novelty.

Novelty is anything new and therefore unfamiliar to your human experience.

On top of this, novelty is also the primary inducer of wonder .

Whenever you consume and enjoy quality content, the pleasure and enjoyment you gain from it will inevitably be some level of wonder.

This wonder may express itself in engrossment, interest, awe, amazement, surprise, delight or satisfaction; in any case, there is an invisible but intrinsic link between quality, novelty and wonder.

.

Whenever you consume and enjoy quality content, the pleasure and enjoyment you gain from it will inevitably be some level of wonder.

This wonder may express itself in engrossment, interest, awe, amazement, surprise, delight or satisfaction; in any case, there is an invisible but intrinsic link between quality, novelty and wonder.

Without novelty, all content would have the exact same format, style, design, prose and ideas. All ideas are the worst idea if they are the same idea. Instead, novelty allows for uniqueness and differentiation between ideas1It is important to note the difference between novelty and orginality. Though novel ideas do encompass truly original ideas, novel ideas also include existing ideas which are presented in an entirely different way..

Both a preconcieved guiding benchmark and a healthy dose of novelty are two of the main ingredients used to create quality. However, there is one more factor to consider... the secret ingredient if you will: authenticity.

Authenticity is more than just a personal style, but revolves around your unique perspective of the world, and how this is expressed in that which you create. As soon as you begin to create for any audience other than yourself, authenticity immediately fades out of the picture.

Importantly, authenticity is the reason AI will never truly replace creators. While AI can to an extent create quality content, it will never truly be able to create authentic quality content. The simple reason for this is that artificial intelligence is artificial — it never has, and never will be able to live a completely human life.

A media’s meta-story is important and it all starts with why it exists. Why must I care? It all begins with one person asking another person to look at it and say: “I made this, want to see?” —Simon de la Rouviere, You can't automate authenticity

Apart of this idea is that authenticity is linked to sincerity. Authenticity is involved in the act of creation something yourself; the sincerity comes when telling the world why your creation exists, and more importantly, why they should care. These two concepts are completely non-existent within AI, and Simon sums up why this is perfectly:

Having established a few of the main ingredients used to create quality, I'm now going to consider a few different methods and techniques through which these ingredients can be used.

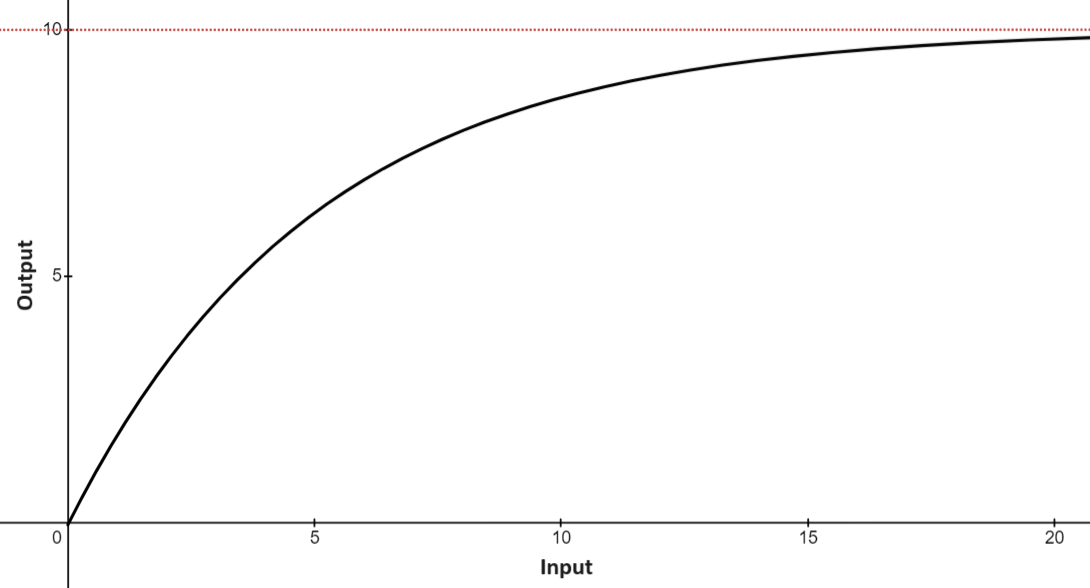

Time, money and any number of resources can be expended to improve quality. In order to better understand the relationship between resources expended and quality achieved, I've tried to portray it visually.

At first, steadily investing resources will provide a proportionate progression of quality. However, as the upper limit of quality is reached, the ratio of resources-spent to quality-improved greatly plateaus. This drop-off in improvement occurs the closer quality approaches perfection, in this instance a score of 10/10. Perfection by it's very nature is impossible to achieve; in this way the more resources spent, the closer quality will asymptomatically approach perfection (though will never truly reach it).

Consider the quality of a bottle of wine. Initially for every extra $10 spent, the quality of the wine (should) improve about $10 worth. However, as you begin to spend more and more, the improvement in quality greatly lessens. Is a $200 wine really that much better than a $100 wine? Or a $2,000 wine much better than a $1,000 wine? Realistically, not by much.

And yet, no matter how much money or resources is invested, a perfect wine will never be achieved2Though that's not to say that you can't get close.

This process by which quality is steadily improved as more resources are expended is more commonly known as iteration. Iteration involves taking a draft or prototype and systematically removing errors and improving substance. Gradually, as the iterative process progresses, flaws should be minimised and coherence should be optimised. Eventually the work should come to a point where it is flawless in form and coherent in style.

Like mis-timed foley or a smudge on the wall, we notice quality more often by the presence of imperfections than by their absence. For this reason, it can be hard to articulate why something is high quality. We can feel it. Like the threshold test for obscenity, "I know it when I see it." —Brian Lovin, Creating quality software

Flawlessness doesn't necessarily translate to perfection. While perfection suggests the greatest imaginable quality, flawlessness is a component inherent within perfection, designating a complete abscence of flaws.

Flaws exist purely on the surface level. In terms of writing this means making grammatical sense; in terms music this means no wrong notes are played; in terms of tools this means no obvious disfigurement; in terms of software this means there are no bugs within the program.

Flawlessness is achieveable. Perfection is not.

While perfection is realistically impossible to achieve, what is possible to achieve is optimisation. Instead of wasting resources chasing the unattainable, optimisation considers the minimum amount of resources required to achieve the maximum increase of quality. Put simply, optimisation is bang for your buck, and lies on the greatest point of bend on the graph. Though it may not achieve the greatest possible outcome, optimisiation will provide the most efficient outcome.

One way to pursue optimisation is to leverage the 80/20 principle, which states that 80% of outcomes result from 20% of inputs. While not a hard and fast rule, it is a useful herestic, and can be applied in a variety of scenarios.

In terms of creating quality, finding the best possible place to allocate your effort comes down to what will engage the widest possible audience. Paul Graham gives a fantastic example in the context of Art.

Art has a purpose, which is to interest its audience... The meaning of "interest" can vary. Some works of art are meant to shock, and others to please; some are meant to jump out at you, and others to sit quietly in the background. But all art has to work on an audience, and — here's the critical point — members of the audience share things in common.

For example, nearly all humans find human faces engaging. It seems to be wired into us. Babies can recognize faces practically from birth. In fact, faces seem to have co-evolved with our interest in them; the face is the body's billboard. So all other things being equal, a painting with faces in it will interest people more than one without. — Paul Graham, How Art Can Be Good

Other examples in terms of art include 3D objects, definite shapes and to a lesser extent particular colour palettes. All these are seemingly universal points of interest among humans.

Essentially, for something to appeal to the widest possible audience, it must appeal to the common ground between all individuals: their humanity.

In music there are certain chord structures and keys which universally sound more pleasing to the ear. In stories there are certain plot structures (orientation, complication, climax, resolution) and themes (good vs evil) which work much better than others. In design there are certain structural choice and features which are far more effective than others.

The trick then is finding the equivalent to a human face in terms of your given niche — the common ground which virtually everyone can appreciate — and then building out from there.

Although this approach is highly effective, it is worth noting that you can't rely on it completely. Though it may provide 80% of your creation, the remaining 20% will require far more of your energy, creativity and resources. This is because it is only this 20% which is differentiating your creation from every other one.

The other pitfall is that by focusing on satisfying the greatest possible audience, your overall creation suffers greatly in terms of depth and breadth of ideas.

This comes back to the fact that simple = accessible ; the tradeoff for increasing audience is typically complexity, in both ideas and design.

; the tradeoff for increasing audience is typically complexity, in both ideas and design.

Within my somewhat convoluted analogy of cooking food as creating quality, I've considered some key ingredients and techniques. Here I'll now consider some recipes, and how these ingredients and techniques can be used together.

If quality is determined by the extent to which something achieves its intended purpose, then creating quality should revolve around determining a purpose, and then achieving it.

As discussed in Defining Quality , these two elements can be split into frontend quality and backend quality.

, these two elements can be split into frontend quality and backend quality.

Apart from simply aiming for a general level of quality, it is also possible to create quality by focusing on each of these inherent key elements individually.

In terms of creating via frontend quality, this involves taking an already existing backend, and presenting it with an entirely new and divergent frontend.

For examples, books can be adapted into many different formats, including graphic novels, movies or tv shows. In each of these contexts, they all share a similar underlying backend (story, settings, characters, plot, etc), but each then individually presented in an entirely different way.

Wider examples of this are everywhere. In the sphere of music this includes remixes, covers and remasters. In the sphere of film this includes remakes, reboots and reimaginings. Even in the sphere of retail, many commercial products and businesses are basically identical and differentiated only by branding.

Although this may seem like a fairly cheap way to produce quality, recreating frontend quality can be surprisingly effective. Oftentimes it's much easier to rely on something with proven quality then to take a stab in the dark in create an entirely novel or original backend.

To create an entirely novel backend requires innovation. Innovation typically involves building upon existing ideas, but can also encompass invention in the same way that novelty encompasses originality3As a rule of thumb, novelty is to innovation as originality is to invention.

One of the main catalysts which is able to produce innovation is inspiration. The way I see it, inspiration is a chain reaction of ideas. All it takes is one prime mover to set off a cascade of adjacent insights, which in one sudden moment lights up in your mind like a naked bulb in dark room. Whether directly or indirectly, all inspiration comes from external stimuli, though this will most likely be consumed quality content.

Apart from focusing on frontend or backend individually, some approaches aim to tackle both at once. One such prevalent approach is the art of world building.

[Worlding is] the art of devising a World: by choosing its dysfunctional present, maintaining its habitable past, aiming at its transformative future, and ultimately, letting it outlive your authorial control. — Ian Chen, Worlding Raga4I have not read (nor even heard of) Ian Chen or his Worlding Raga. This quote was taken from Jay Springett's excellent essay collection World Running

In its most easily recognisable form, world building is typically a feature of science fiction or fantasy. Stereotypically this may involve a futuristic dystopia/utopia, a secret magical society or a completely alien environment.

The quality of world building, and to an extent the quality of the work within a world, comes down fundamentally to the level of detail employed. Considerations may include history, geography, culture, ecology, politics, economics and religion; generally, the more detail provided, the more realistic a world will seem. However, because explicitly presenting this detail is disarstrously boring, the trick then is conveying this detail implicitly.

Initially world building begins with creating the world itself, and by doing so establishing its underlying structure (backend). Subsequently, the work itself, whether it be the actual writing, directing, music making or otherwise, is then incorporated directly within this world (frontend).

World building enables richer, more immersive experiences in virtually any work of creation.

Examples of world building can also extend far beyond stories told by books or film; consider concept albums, game designs, theme parks, extensive marketing campeigns, historical period exhibits, virtual environments, cultural lore , fandoms, even entirely new art movements.

All these and many more encapsulate world building.

, fandoms, even entirely new art movements.

All these and many more encapsulate world building.

Creation in all its forms encapsulates many facets; innovation, iteration, experimentation, exploration, reflection... But, as with cooking, there is no one formula to make a delicious meal. Scores of ingredients, techniques and recipes can all be used to make any kind of culinary creation imaginable.

No matter how or what you create, in the end you are ultimately crafting an experience. Experiences are how we perceive life in the context of time, so the importance of quality is helping people get the most out of their time. Remember, a good meal is not only sustenance for the body, but also sustenance for the mind.

← Discovering Quality Narrative Tension and Meta-tension →